Guest blog by Eric C. Reuter

Last year in 2014, I was able to spend time in our summer cabin staring in March, which is much earlier than usual. I had never been there before early May in the past, as it is quite cold to be in an unheated and un-insulated summer cabin in winter. It turned out to be an amazing time for very early spring moths, although a very challenging place to live for a couple months.

This is what the view from in front of the cabin overlooking the lake was like when I arrived:

Before the snow had even melted, and the ice cleared from the lake, I had the mothing sheets and lights out in hopes that I would see some species that I knew *should* be there, based on the abundance of host plants for them, and the region I am in.

Before the snow had even melted, and the ice cleared from the lake, I had the mothing sheets and lights out in hopes that I would see some species that I knew *should* be there, based on the abundance of host plants for them, and the region I am in.

I had always longed to get to see the Feralia species moths. Those green gems that feed on pines and Hemlocks and appear in early spring, with common names like “The Joker” and “Comstock’s Sallow”. It was a few of those species I would look at with great envy in The Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America almost every time I paged through it. But I had never seen a single one before. I had always been too late to arrive at the cabin.

By the end of March and into Early April, daytime temperatures were reaching the 50’s, with night time lows still often below freezing. But for the first few hours after sundown, and sometimes well into the night, I started to see moths showing up at the sheets, despite the frigid temperatures. Turns out these early fliers are even hardier than I had anticipated.

Each year for the last 7 years, I was at the cabin mothing the late spring and summer and early autumn and had seen an incredible diversity, but never before had I seen the coveted early spring moths, I kept wondering if they were really there, if I would ever see them.

In 2014, that all changed. In fact, it was over-the-top crazy with all that I was able to see. I was hoping to see a few of those species. I saw many hundreds.

I will never forget when I saw my first “Joker” – Feralia jocosa, this incredible striking green moth sitting on my sheet when it was 39 degrees outside. I could barely contain my excitement, as I called my fiancée Lisa to tell her, and to get her up there for a visit as soon as she could.

This was to be the first of many, many sightings. I compiled a huge assortment of photographs of Feralia jocosa, F. comstocki and a few of F. major over the next month, when they abruptly stopped showing up by early May….the time of year I would normally be arriving. I got to see many of the rarer brown form and intermediates as well.

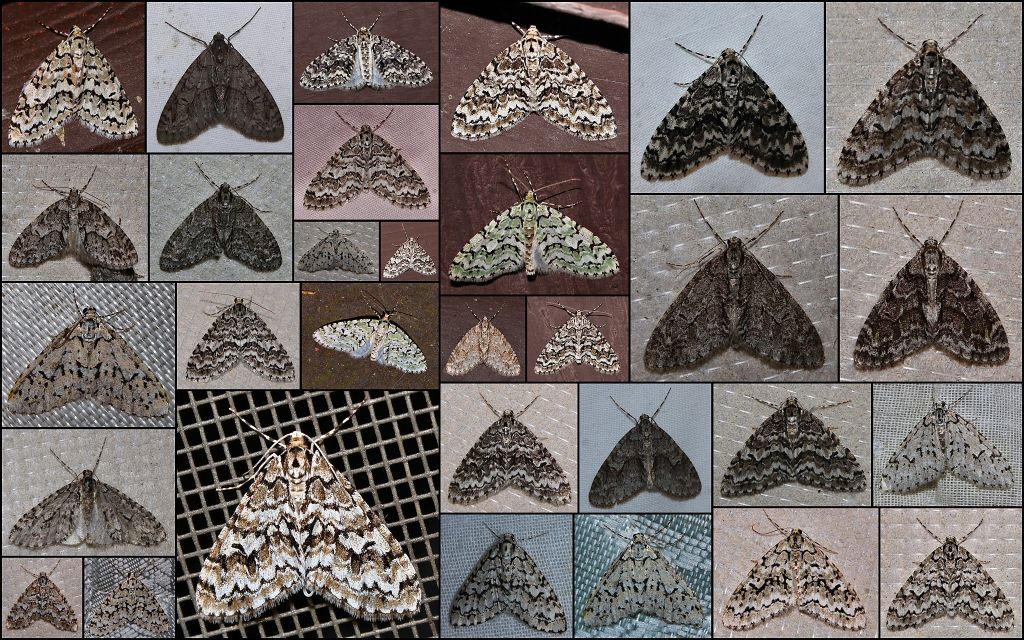

This is just a fraction of the Feralia jocosa (Joker moth) varieties seen. Every shade of green, olive and brown (considered rare) were represented.

As luck would have it, a host of other early species showed up as well. Many of which I had also never seen before. With each new moth species and in the numbers I saw of them, I was truly amazed at how they flourish in conditions you wouldn’t expect to see moths in. Extremely cold nights, days not that much above freezing, I would check the sheets with a heavy coat and gloves on! The moths didn’t seem to mind.

Feralia comstocki (Comstock’s Sallow) was the second Feralia species to show up a few weeks later. They were noticeably larger than F. jocosa and have three striking black bars surrounding the reniform spot on the forewings. They too displayed some dazzling shades of green and great variety. Below: Feralia comstocki

In addition to the stunning Feralia species moths, a number of other wonderful early spring moths graced my sheets. Large numbers of “Scribbler” moths Cladara atroliturata in both green and gray forms, along with the similar Cladara limitaria – Mottled Gray Carpet Moth appeared starting in April and into May:

Some of the other moths I got to see in early spring were equally wonderful, with some being uncommon species. Below the very similar (L) Kent’s Geometer (Selenia kentaria) and ( R), Northern Thorn (Selenia alciphearia). Both of these moderately large moths are seldom seen.

Also present were the large and very colorful Zale species moths, with their extremely variable patterns and colorations. These appeared in larger numbers during early May than at any other time during the year, and were a wonderful surprise for me. Below is a sample of what we saw:

There were many other species that we saw during these early months, which would take far too much space to display here, but included: Xylena curvimacula, Phigalia strigataria, Phigalia titea, Lithophane grotei, Lithophane petulca, Lithophane baileyi, Pyreferra citrombra, Orthosia revicta, Orthosia rubescens, Cerastis tenebrifera, Anticlea vasiliata, Psaphida resumens, Copivaleria grotei, Achatia distincta and many others. Shown below is the unique looking Xylena curvimacula – Dot-and-Dash Swordgrass Moth

One particular “rarity” and a highlight was this “lifer” moth for me: Cerastis salicarum – Willow Dart Moth, which showed up one evening with 4 others of its kind on one of my sheets nearest the cabin.

During these early months I relied on using a couple of locations on the property for lighting and sheets. First was large professional sheet where I set up a Mercury Vapor Lamp along with a 25W UV lamp (hanging on the sheet itself). This was placed deep in the woods that surround the cabin, so that it would draw in moths from a larger area. Additionally, we put smaller sheets with UV and CFL (Compact florescent, the “twisty” bulbs) lamps on the house and inside a small alcove near the door. This provided a more sheltered (and somewhat warmer) location to attract moths and to be more suitable during inclement weather when the primary sheet could not be used.

This time of year in the mountains of NY is challenging and much different than the lush and warm summer months with regard to mothing techniques. Most of these moths fly early at night and just for a short period, so in order to maximize the period of time available, all lights were on at least an hour before sunset. The dense woods is already very shaded and quite dark by that time of day in winter and early spring, so getting a “head start” seemed to work better. Having multiple locations also produced some interesting results. More of some of the species were drawn to the house sheets than to the large sheet deeper in the woods, and some were only seen there (and vice-versa). I am not sure what that resulted from, but it did provide some great results. Perhaps it was that they sensed the heat coming from the cabin (which bleeds warmth due to it being uninsulated), or that it was calmer with respect to wind. It will be interesting to take a closer look at that this year and in future years when we can spend more time there in the earlier months.

The most incredible thing I discovered was the amazing number and variety of moths that could be seen this early, with the climate and temperatures being so much cooler and the dense forest devoid of most underbrush and other plant growth. I recommend to anyone who is interested, and who lives in the colder climates to start their mothing season perhaps a good bit earlier than they may have otherwise thought would be productive. The hardiness and persistence shown by the species I saw and photographed was pretty astonishing. I took a chance on trying to see what was “out there” when I expected hardly anything, and was rewarded with an incredible mothing experience I won’t ever forget. If you give it a shot, you may be very pleasantly surprised as I was.